On Slacktivism

What it really means to raise the bar in real estate

Originally Published At Inman News, May 2012

“Slacktivism: The act of participating in obviously pointless activities as an expedient alternative to actually expending effort to fix a problem.”

Urban Dictionary, quoted by Sarah Kessler in ‘Why social media is reinventing activism’

One thing the real estate industry feels particularly acutely at the moment is change. Market change, financial change, technological change, even customer change. Our industry is undergoing one of the most seismic sets of changes it has ever seen, and many who have built their businesses around traditional perceptions of customer service, marketing or even pricing, are beginning to become casualties. In many ways, the real estate industry’s embrace of, or struggle to embrace, social media, is a perfect crystallization of all of these issues, as those platforms personify the acceleration of the pace at which information is shared, disrupt existing marketing models, and change the way the web is consumed, away from pages, and more towards conversations between people.

At the heart of many discussions surrounding the use and adoption of social media, is the questioning of its real-world effectiveness. Can these platforms truly impact long-lasting, meaningful change in a manner that goes beyond simply ‘liking’ something? Can truly effective change be achieved, or is it simply, at massive scale, that we’ve submitted to feel-good clicking, rather than actual participation and association with a cause? It’s true that these platforms have recently had a strong (or at minimum well publicized) hand in the toppling of regimes, the resignation of elected officials, and even the financial support of the democratic process itself, but how are these platforms changing traditional methods of collective activism? Many in the real estate industry purport to be using social media to raise levels of awareness for brands, their own agendas, and product launches, but one with much discussion, over the long term, has been the ‘Raise The Bar’ discussion, currently one of the largest and most engaged groups within the industry on Facebook. The group discusses many issues, from improvements in agent perception, the future of brokerages, professionalism, and best practices. It’s become a concentrated hub of online activity, in many ways, for discussing the multitude of problems the industry is currently up against. However, in order for such a group to be effective, I argue that it needs to result in real-world action, real-world results, and needs to break from the conversation, into inspiring actual change, either through lobbying local associations (for example to change entry requirements for agents), or broader, mandated changes that force change at scale. While casual ‘me too’ engagement at scale leads to cumulatively more (but smaller) strong advocates capable of making that change, it brings into question how effective such social organization can actually be when exclusively housed in these platforms.

“Facebook activism succeeds not by motivating people to make a real sacrifice, but by motivating them to do the things people do when they are not motivated enough to make a real sacrifice.”

Malcolm Gladwell, The New Yorker: ‘Small Change. Why The Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted’

This is the question Courtney Boyd Myers explores in response to Malcolm Gladwell’s provocative exploration of online activism for the New Yorker. Gladwell argues that modern forms of social media cannot lead to the same types of high-risk activism that resulted in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and he draws several parallels between the faux-activism of changing your avatar in support of a cause, and the real-world activism of lunch counter sit-ins. In essence, is clicking the ‘like’ button enough of an actionable endorsement? While Gladwell says no, several high-profile advocates of social media have written in strong opposition explaining why the answer is an emphatic yes. How ‘liking’ or ‘sharing’ something is not necessarily a call to action, but more of a measure of mass agreed, mutual sentiment. The incredibly powerful reach of social platforms, purely attributed to their scale, makes it much easier to self-organize today because there’s simply a faster, easier way to harness casual enthusiasm, and while it’s true that, as Gladwell suggests, real activism is highly reliant upon years of grass-roots offline cause-building, social media (as he also agrees), has the capacity to accelerate the growth of these causes, often with explosive and destructive ends. Gladwell argues that causes need to have the foundation of real-world activism strongly in place, across large groups of people, before social media can begin to be effective. Digital social media organization in and of itself is ultimately impotent, and nothing more than chatter dissolving into the perpetual noise of a news feed.

Echoing both Boyd Myers and Gladwell, David Leavitt explores the idea that in order for a movement in any form to truly be strong, it needs to have significant strength outside of its reliance upon technology. Leavitt argues that in order to be effective, organizations looking to create long-lasting meaningful change need to create varying levels of action, so that advocacy doesn’t devolve into an endless series of Facebook ‘likes’. Indeed, groups formed around causes often inadvertently focus upon relentless negativity, under the guise of support and advocacy, and take hold in exploring the problems, rather than the solutions. Unfortunately, this results in a somewhat inaccurate impression that the situation is, as Nicholas Kristof accurately describes, an “abyss of failure and hopelessness. Who wants to invest in a failure?” It’s true that when it comes to social media, a catchy video, rather than reports and statistics, or even the hard evidence, can garner more support, or at least awareness of a cause, and in many ways, one of the most effective ways to market industry improvements such as ‘Raise The Bar’ is to rebrand the issue to gain more support.

There have been many recent examples of social media activism at work, from SOPA and the efforts to change proposals to internet regulation, to the ‘It Gets Better’ campaign which aims to support and inspire young people facing harassment, through to advocacy organization Invisible Children’s KONY2012, which came to widespread attention through the sharing of a lengthy 30 minute video which, at the time of this writing, has been viewed over 90 million times. While KONY appeared to come out of nowhere for many who were exposed to it, the movement against the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony has its roots in some questionable sources, tenured over many years. It was the culmination of years of real-world, grass-roots activism efforts, that were propelled to wider consciousness only recently through the use of YouTube.

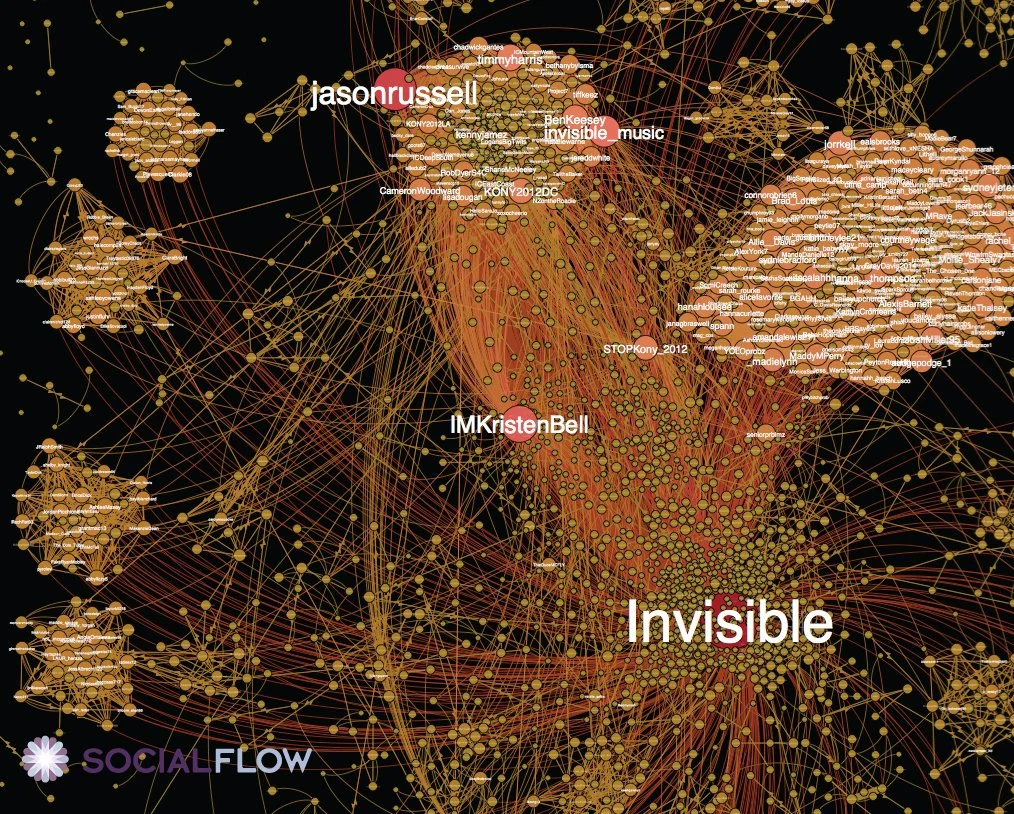

The early network growth of KONY 2012, analysis by SocialFlow (Source)

Writing in Forbes, Anthony Wing Kosner explores KONY’s origins, and plots the journey the movement took and how the explosive spread of the video was only the last piece of a very large and complicated puzzle of real-world activism. Interestingly, and against the trend of how most online ideas originate and spread, the movement has its origins not on either the east or west coasts, but in what Kosner terms ‘Silicon Prairie’ , something that appears to be on the rise online as reflected by platforms such as Pinterest, where online adoption phenomenons are originating at scale and digital customer use from the heartlands, and then spreading outwards, the reverse of many early adopter cycles that begin either in Silicon Valley (San Francisco) or Silicon Alley (New York City). Referencing the substantial data analysis from social tracking service Social Flow, Kosner charts the spread of the original video, where it began to trend on Twitter first, and specifically why certain geographies appeared to know and understand the video faster than others. Importantly, the notion of attention philanthropy, as promoted and encouraged by those backing KONY over long periods of time, activated substantial online activity, and allowed the video and its message to spread incredibly aggressively.

“Dense clusters of activity that were essential to the message’s spread: networks of youth that Invisible Children wanted to promote this video, deploying the grass-roots support of these groups was essential.”

Anthony Wing Kosner: ‘Suspicious Sequel, The Social Flow of KONY2012 Is Not What You First Thought’ (Forbes)

When looking at the data of online activity, those dense clusters of activism were surprisingly geographic, with the earliest signs of trending activity in Birmingham, Alabama. In fact, the issue was trending in that region before the video had been posted online. Social Flow’s data suggests that the initial growth of the online distribution of KONY’s message was heavily supported by Christian youth, often identified and associated with posting psalms in their bios for example. Indeed, Invisible Children had been targeting public high schools and church groups across the Southern United States as far back as 2005 — seven years before the video exploded one morning on Facebook.

“Coming in January we are trying to hit as many high schools, churches, and colleges as possible with this movie. We are able to be the Trojan Horse in a sense, going into a secular realm and saying, guess what, life is about orphans, and it’s about the widow. It’s about the oppressed. That’s God’s heart. And to sit in a public high school and tell them about that has been life-changing. Because they get so excited. And it’s not driven by guilt, it’s driven by an adventure and the adventure is God’s.”

Invisible Children co-founder Jason Russell, Quoted by Kosner in 2005 Christian conference in San Antonio (Audio Recording)

As Kosner illustrates, the groundwork for producing a video that would be spread aggressively online, to the point where 90 million people had watched a 30 minute video (in itself an impressive achievement), had been laid out prior for many years, and like most instant hits, KONY was far from an overnight success. It’s obvious to understand where Christianity has an obvious legacy of alignment with movements of social justice, but Kosner follows the money, and finds that Invisible Children has backers with not only strong social conservative political views, but also ties to anti-gay organizations (such as the National Christian Foundation), and politically motivated groups with powerful lobbying budgets. While Kosner describes how these highly politicized organizations have disbursed funds to several anti-gay groups, current Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has also promoted the inclusion of anti-gay agendas in his policy making, fostered by, as Kosner continues, support from social conservative groups that also coincidentally fund Invisible Children. Indeed, Russell encouraged those targeted students to engage in “extremely low-key, or stealth evangelism”.

Sudarsan Raghavan goes even further, explaining how Invisible Children’s political ties to ‘The Family’ (a Christian Political Fraternity) explained how the issue of overthrowing Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony was potentially (and allegedly) fast-tracked to the desks of elected officials in Washington. Again, following the money, Raghavan explains how Invisible Children’s primary product isn’t actually aid to the African in need, but rather film production, advocacy, merchandise and assisting lobbying efforts within the U.S. State Department for increased military presence in an oil and mineral-rich area of Eastern Africa. This approach closely dovetails the 2007 AFRICOM military initiative signed into effect by then President Bush, perceived by some as aimed at reducing the influence of China and securing U.S. reserves in Africa. A strong counter to this perceived view, well laid out by Robert Moeller can be found here (although he does suggest that the organization is still in place to promote American interests).

“[AFRICOM] will strengthen our security cooperation with Africa and create new opportunities to bolster the capabilities of our partners in Africa. Africa Command will enhance our efforts to bring peace and security to the people of Africa and promote our common goals of development, health, education, democracy, and economic growth in Africa.”

White House Statement: ‘President Bush Creates a Department of Defense Unified Combatant Command for Africa’

Further criticism of the film itself argues that the main focus of the KONY2012 film relies heavily on interviews conducted between 2003 and 2006 with Ugandan villagers, many years prior to what is happening right now. Combined with the incredibly public mental breakdown of Jason Russell himself, the closing of comments for the initial YouTube video, and the emergence of potential ties to evangelical groups (for example, Russell was also an undergraduate student at Jerry Falwell’s ‘Liberty University’ in Lynchburg, Virginia begin to swiftly erode the equity and positive will built around the movement’s perceived causes. Invisible Children is not a registered charity, however, its finances are published online, where we can learn that only 32% of the $8.6 Million recently raised by the organization went to physical, meaningful aid, whereas the remaining 68% went on salaries, travel, transportation and film production. These are figures, politicized discussions, and substantial issues with very severe real-world consequences that many simply clicking ‘like’ on a YouTube video in slacktivist, peer-approved support of a cause which their friends had forwarded to them, would simply be unaware of. It’s buyer beware on steroids.

To go further, the influence of celebrity upon an issue such as KONY can further complicate matters. Will Krugman combines the discussion with that of the risks of GroupThink, the process whereby a pool of people unanimously decide a solution to a problem, and where the cohesion and growth of the group itself takes precedence over dissenting opinion and constructive discussion. The solution reached often doesn’t solve the problem at hand, has little basis in reality, and in some cases, can actually make the problem much worse. Krugman skillfully explores the high risk, and high reward of social media activism, referencing SOPA as a successful example, but KONY as one that isn’t.

“You need to speak up. You have to listen to the voice in your head telling you that something seems off, and to not get your advocacy advice from Kim Kardashian.”

Will Krugman: ‘The Risks Of GroupThink With Social Media Activism’

This is the explicit risk with activism within social media, and one the real estate industry is seeing, albeit at a much less impressive scale, around discussions concerning syndication, and raising the bar. The capacity to participate through social platforms, essentially from your couch without meaningful action resulting in real-world change, holds the potential to be damaging to the perception of the industry, productivity, and perhaps most importantly, clients. Our own efforts to align with causes can actually also be harming those causes themselves. Many inside and outside the real estate industry, spread the word on Facebook and Twitter in the strong, and passionate belief that they are doing the right thing, simply without realizing the consequences of what they’re doing. For example, as Rob Hahn has consistently argued, if the real estate industry raises the entry requirements in order to be an agent, or if there’s a strong enough voice for uncoupling the MLS from NAR, then what naturally results is a significantly lower number of real estate professionals. This has enormous consequences not only for the individuals who wouldn’t make the cut, but for NAR themselves of course. Lobbying power begins to get disrupted, and the issue begins to further fragment, instead of unite. These are consequences of building ‘movements’ online surrounding raising the bar as one example, and unless it results in real-world change, instead of perpetual chatter within Facebook, unless it leaves the digital space, as the syndication issue has begun to for some smaller brokerages, it remains, and will always remain, impotent.

Let’s take another example from outside the industry. What do all KONY’s YouTube video’s views really add up to? How does all the online social ‘awareness’ of an issue actually result in helping people or achieving the goals of the cause? Perhaps incorrectly, many campaigns assume that visibility is a direct path to concrete action, and that the best venue for such action is the one where people are spending the most time: Facebook. However, this is about as true an assumption as advertising having a 100% conversion rate, or believing that online users behave in rational, linear ways. Unfortunately, the rampant spread of slacktivism, whereby clicking a link or tweeting becomes important, just because it shows minimal conviction and peer-encouraged affiliation with an issue, does demonstrate a shift in that those people sitting on the couch who were previously doing nothing are at least now doing something, has value, especially at scale, and this is the primary argument against Gladwell’s initial article. It’s true that however questionably effective a cause may be, internet protests make headlines, and therefore attract attention, which indirectly begins to cause change. Is this really activism, or just a shift in method? How effective and meaningful is that change? Perhaps this says more about how those headlines are generated, rather than the activist efforts themselves.

As Rachel Sklar neatly argues “social media activism is a gateway drug to real activism”, and while it’s very true that social media makes activism contagious, it still needs the substance of real-world, offline activism to be in place first, before it can spread, and that’s where the misperception begins to happen. Causes without that real, tangible substance that solve real-world problems with actual change, are ultimately meaningless. In one of the most passionate and thoughtful responses to Gladwell, the always insightful Mathew Ingram in his ‘Memo To Gladwell’ series for GigaOm, offers that Gladwell essentially dismisses social media as irrelevant to social activism, implying that it’s ephemeral, and predicated upon weak ties. However, Ingram skillfully counters that whereas Gladwell draws a clearly defined line between the online and offline worlds with his arguments, for an increasing number of people, those worlds are blurring aggressively, to the point where they are almost the same thing in the era of ubiquitous mobile access.

Citing writer Zeynep Tufekci’s stellar work in the field of technosociology with the blurred line between both worlds, Ingram argues that to even make such a distinction shows a fundamental misunderstanding as to how information spreads, ideas are shared, and causes grow. Tufekci points out that ‘Facebook plays a key role in a collective action / information cascade’, fueling existing movements with often incredibly aggressive momentum, propelling causes to the forefront of our attention. This, of course, is also a customer pattern of behavior currently of great interest to digital marketers. Out of these information cascades, she argues, comes real-world action, such as was the case with SOPA. ‘Cascade’ is an appropriate term for something fueled by a gathering momentum, especially online, and whenever we see these kinds of stories ripple through a news feed, uniting users across the globe in a shared, common conversation, it’s easy to see why they result in that same momentum being carried over to the real world. However, are there costs associated with joining in with this collective behavior? Are there consequences of online dissent, even if it’s as part of a large group? Ingram describes the problem:

“No-one wants to take action by themselves because of the consequences, but since there is no way to be sure that anyone else is going to join them, revolution becomes a stalemate.”

Mathew Ingram: ‘Memo to Gladwell: Social Media Helps Activism, And Here’s How’

Reminiscent of the collective group decision making of James Surowiecki’s ‘Wisdom Of Crowds’, where individual responsibility is abdicated and decentralized in favor of submitting to the collective will of the herd, by joining in with the ‘me too’ liking, commenting and sharing via social platforms, it allows us to perhaps align with causes in a way that we wouldn’t in the real world, therefore carefully encouraging participation in a way that’s new to us. Simply put, it’s easier to get lost in a sea of a thousand likes. And whereas collective action barriers, as both Ingram and Tufekci continue, have usually centered around co-ordination and communication problems (why effective grass-roots movements used to take years to build), those same problems of mass acceleration, distribution and awareness are much diminished. Today, getting the word out is far easer in an age where everyone can be a publisher. In fact, social media explicitly encourages the building of social momentum, especially though the use of the ‘like’ buttons outside of Facebook itself. It’s a synthetic, highly stylized and often false sense of connecting to a larger community, that appeals to chemical release in the brain, as well as a visceral need to feel part of something larger than ourselves. As Ingram expertly concludes, the great irony of the Gladwell piece is that the impact of social media upon revolution and social change is that it deliberately creates ‘tipping points’, the same concept which in itself propelled Gladwell to wider appeal.

Collective action, like any other kind of cumulative online brand building, takes place based on the slow, steady build-up of small events, and seemingly unconnected discussions, over long periods of time. The difference with social platforms is that they bring a much needed stimulant to that process, and incredible scale.

“Sticking a pamphlet in each door has been replaced by email lists in a lot of places. Standing on the corner with one of those megaphone things has become Twitter. Petitions can easily be shared on Facebook instead of being taken from door to door or standing outside the supermarket. And thousands of people can organize for rallies and demonstrations in almost no time at all. And in some cases, stories that might have been overlooked by the mainstream media are kept alive by online activists, as in the Trayvon Martin Case.”

Michel Martin: ‘Social Media Changing The Nature Of Activism?’

The notion that social media provides a ‘gateway drug’ for deeper engagement with causes, across large, diverse networks of people is also something explored at length by writer Brian Solis. In his piece ‘Malcolm Gladwell, Your Slip Is Showing’, he discusses why everyone now contributes to the evolution of culture and media, to the point where it doesn’t matter what platform is used, as it’s the network of people that’s truly important, moving the discussion away from tools and ties, and more towards aligned interests and shared emotions. Traditionally an incredibly difficult thing to measure, quantify and even optimize, Solis’ idea of the spontaneous, simultaneous spark of strong, weak and temporary ties between potential online activists allows causes to propel the distribution of information in incredible, and never-before-seen ways. Diverse groups aligning around interests, inside and outside of industries, allows ideas to spread rapidly, especially if they are within densely-connected networks, such as a local market. The tools, such as Facebook, simply allow those networks to connect faster by creating denser, more cohesive networks. For example, most of us are part of several networks online. They might be friends, professionals, family, perhaps even just random people you’ve accepted. The denser the network, in terms of how closely (and frequently) the individuals within those groups interact online, the faster the information will spread. This is particularly acute during an event of breaking news, or something truly exceptional, and the phenomenon of ‘I found out about it first from my friends on Facebook’ is an increasingly common one. Incredible events bring us together, they activate groups and make them denser, and therefore more powerful online.

Gladwell’s argument, as most of the counters suggest, is that he essentially denies the strength of social culture, or at least the social culture the web is increasingly fostering, characterizing it as being almost exclusively predicated on a large volume of weak ties, and that information struggles to pass swiftly through different networks such as these. This same argument, of course, could be used in opposition to social media in oppressive regimes, where it can just as easily be used as a tool to monitor collective online dissent, as well as galvanize collective, activist activity.

In one of the best pieces concerning the discussion Gladwell sparks, Alexis Madrigal, writing in The Atlantic, goes further on the idea of the strength of social media’s weak ties, again countering Gladwell’s assertion that weak-tie networks don’t have the dedication or structure to take on established and entrenched real-world power structures. Madrigal suggests that while it’s indeed true that modern communication technologies such as social platforms can actually reinforce existing power structures, the idea of a leaderless, unorganized, homogenous mass of online opinion, is actually a myth.

“Twitter acts as a kind of human recommendation engine, in which I am the algorithm.”

Alexis Madrigal: ‘Gladwell On Social Media And Activism’

Madrigal rightfully points out that face to face is simply not the only way to build strong ties, with many experiencing incredibly strong ties online having still never met the other person in the real world. Also, a tremendous volume of weak ties still cumulatively adds up to a lot more strong ones than you’d ever have had before, and that importantly, both weak AND strong ties are able to co-exist within the same network. They simply aren’t the ontological opposites they are often portrayed as. Again quoting Tufekci’s work, Madrigal offers that ‘large pools of weak ties are crucial to being able to build robust networks of stronger ties — and internet use is a key to this process’.

To suggest that social networks are leaderless is to make the same comparison of grass-roots movements in the real-world. In many ways, either through deferring to the group’s administrator, or to the most vocal commenter, those leaders naturally emerge online as part of the conversation. Of course online groups, especially in social platforms, can have leaders, strategy, and clearly established lines of authority. These exist in almost all of the examples I’ve discussed here, including real estate’s ‘Raise The Bar’ group. But to what effect? How do a million small protests, however insignificant, actually add up to something powerful? Anil Dash, echoing both Ingram and Solis, proposes that what’s new about social platforms is that they enable and encourage a new type of synthetic personal politics, one which convinces people that changing your avatar is actually a meaningful form of activism. Drawing effectiveness parallels with actual protest marches, which, he argues, also affect little change overall, Dash points out the legacy of quiet, collective civil unrest already playing out, especially online:

“We have had an enormous and concerted act of social disobedience play out over the past half-decade, where millions have decided that the present regime of intellectual property law and corporate control over the way we communicate is no longer tenable.”

Going further, Dash puts it in even simpler terms:

“The people who actually make things happen aren’t just sitting around clicking ‘like’ on things online.”

Anil Dash: ‘Make The Revolution’

And that’s the primary criticism of how this specifically applies to the real estate industry. Until the sharing, liking, commenting and group dynamics begin to translate to real-world action, they will remain confined with the social platforms themselves. While social is already highly proven to act like adding rocket fuel to a cause, it has to be a real-world one first, with concrete, actionable goals, defined timeframes, or other items of urgency or gravitas. Without them, it simply dissolves into the news feed, and remains within the realm of online, often ineffective discussion. Many argue that simply ‘keeping the conversation going’ is a goal in itself, but if the goal is to truly ‘raise the bar’, then it has to cast its net wider into the real-world, and begin to result in concrete steps acted upon, for example, by local associations.

Whereas Gladwell points to the specific risks associated with activism, such as the present threat of violence and personal harm in the case of the civil rights movement, these cannot be used as some form of litmus test or measure of what constitutes the strength of a cause. He stresses that such high-stakes activism simply doesn’t exist on the web, which make social activism somewhat of an oxymoron. Affiliating ourselves with causes, simply for the sake of peer approval, is one way that awareness has spread through the social web, but it’s also not uncommon for those same alliances to blossom into real, offline friendships. Maria Popova proposes that online communities not only broaden our scope of empathy, but that, going deeper, empathy is actually the missing link between awareness and action. In decentralizing responsibility, she argues, there’s a monumental impact upon collective awareness.

In order of action, she describes it as follows:

“The power of the social web lies in the sequence of its three capacities: To inform, to inspire and to incite.”

Maria Popova: ‘Malcolm Gladwell Is #Wrong’

Simply put, big change comes in small packages, especially online, and the rudimentary communication amongst individuals in real-time allows people to unite around a common goal as never before. In aligning around a cause, to the point where online activism becomes real-world change, is dependent upon empathy, the density of the networks engaging with those causes, and the strength of the content and conversations being produced inside them. Until such time as this moves beyond the slacktivism currently so prevalent within real estate groups online, and more into the realms of information, inspiration, and truly grasps the power to incite meaningful change, those conversations will never leave the groups that simply archive them.

Further Reading:

Jennifer Aaker: ‘The Dragonfly Effect’

Courtney Boyd Myers: ‘Has Social Media Reinvented Social Activism?’

Vinton Cerf: ‘Internet Access Is Not a Human Right’

Michael Clausen, A Conversation On TED: ‘How Effective Is Social Media Activism (And ‘Slacktivism’) In The World Today?’

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi: ‘Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life’

Anil Dash: ‘Make The Revolution’

Monica Eng: ‘Social Media Activism Transforms Food Industry’

Malcolm Gladwell: ‘Small Change. Why The Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted’

Mark Glaser: ‘Mediatwits #44: Social Media’s Role In Activism, Trayvon Martin; Pinterest’s Legal Drama’

Mikki Halpin: ‘Start With Listening, Not Talking’

Yong Hu: ‘The Revolt of China’s Twittering Classes’

Matthew Ingram: ‘Memo to Gladwell: Social Media Helps Activism, And Here’s How’

Matthew Ingram: ‘Malcolm Gladwell: Social Media Still Not a Big Deal’

Matthew Ingram: ‘Memo To Malcolm Gladwell: Nice Hair, But You Are Wrong’

Invisible Children: ‘Financial Disclosure Documentation’

Patrick Henningsen: ‘Exposing KONY 2012 And Invisible Children’s Right-Wing Evangelical And CIA Relationship’

Beth Kanter: ‘The Networked Nonprofit: Connecting With Social Media to Drive Change’

Sarah Kessler: ‘Why Social Media Is Reinventing Activism’

Anthony Wing Kosner: ‘Suspicious Sequel: The Social Flow of KONY 2012 Is Not What You First Thought’

Nicholas D. Kristof: ‘Boast, Build And Sell’

Will Krugman: ‘The Risks Of Groupthink With Social Media Activism’

David Leavitt: ‘Does Social Media Help Or Hurt Activism?’

Stephen Littlejohn: ‘Theories of Human Communication’

Geoff Livingston: ‘Turn Slacktivists Into Activists With Social Media’

Gilad Lotan: ‘See How Invisible Networks Helped A Campaign Capture The World’s Attention’

Alexis Madrigal: ‘Gladwell On Social Media And Activism’

Matthew C. Nisbet: ‘iProtest: Social Media And The Evolving Nature Of Political Activism’

New York Times Room For Debate: ‘Fighting War Crimes, Without Leaving the Couch?’

NPR: All Tech Considered: ‘Social Media Changing The Nature Of Activism?’

Chris Paine: ‘KONY 2012's Struggle To Remain Visible’

Maria Popova: ‘Malcolm Gladwell Is #Wrong’

Pamela Rutledge: ‘Four Ways Social Media Is Redefining Activism’

Brian Solis: ‘Malcolm Gladwell, Your Slip is Showing’

Biz Stone: ‘Biz Stone On Twitter And Activism’

James Surowiecki: ‘The Wisdom Of Crowds’

Zeynep Tufekci: ‘Social Media’s Small, Positive Role In Human Relationships’

Zeynep Tufekci: ‘What Gladwell Gets Wrong: The Real Problem is Scale Mismatch’

Peter Walker: ‘Kony 2012 Charity’s ‘Cover The Night’ Protest Draws Less Visible Support’

David Weinberger: ‘Gladwell Proves Too Much’

Robert Wright: ‘Kony 2012' Night Arrives at Last’