Inside The Mind Of A Millennial

Sotheby’s International Real Estate Annual Leadership Conference, Punta Gorda, Florida 2016

Coldwell Banker Annual Conference, Chicago 2015

Good morning everyone, and thanks so much to Premier Sotheby’s International Realty for inviting me to share some of our perspectives around younger consumers with you all today. As you can imagine, when the offer from Lena came in, I was thrilled to escape the cold and snow of New York.

As you can imagine, The New York Times is going through a period of seismic change at the moment, unprecedented in its 160 year history as we make the transition from print to digital. The product group at The Times is responsible for shepherding the organization through this transition, and I’m the Real Estate component of that. It’s an incredibly exciting time to be there, with some fantastic business problems to work on together with brokerages. In many ways, we think the issues faced by The Times run parallel to the issues and challenges faced by the Real Estate industry.

Aggressive fears of disintermediation fueled by technology, especially in a world that runs on free, significant challenges to our value proposition based on the increasing commoditization of our products elsewhere online, and perhaps most importantly, smarter and smarter users, especially younger users, who are more than willing, and now able, to do a lot of that work on their own.

But while our shared problems are large, I believe the collective solutions are similar as well. Staying strong to the core of one’s value proposition is more important than ever in this kind of environment. Customer service, and creating amazing experiences that truly delight customers and users is paramount to sustaining a healthy, long-term relationship and fueling repeat business.

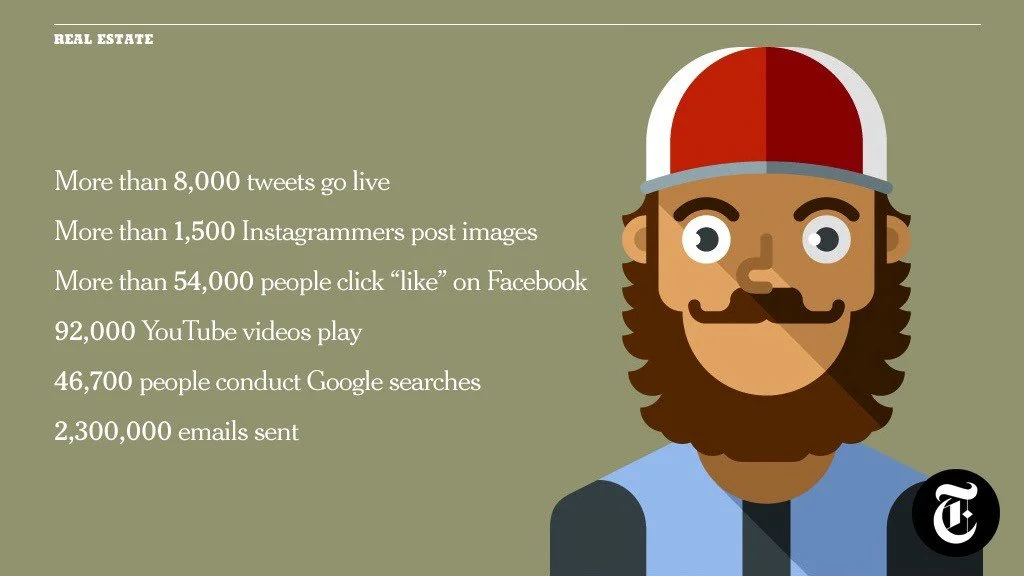

As is staying the course in a climate of perpetual change. We live in a period of unprecedented cultural change, where more content is being produced and consumed than ever before. With more and more ‘stuff’, that sense of overload can be very real, especially for agents who’s value is already in question from their customers.

For some context, here’s what happens on the internet every second. Pretty powerful, right?

But as I hope to demonstrate today, there’s many, many reasons for optimism, especially for the folks in this room.

So today I’m going to talk a little about how The Times, and many brands beyond The Times, are connecting with younger users, creating value based on a truly long game strategy, and really understanding that seismic shift in user behavior, as accelerated by technology.

And if you’re interested in cultivating long-lasting readership, actual content engagement, and deep, considered, digital relationships, gaining a true understanding of what's meaningful to those who are the future of your business offers insightful focus in a world already driven beyond extreme distraction. It’s also a way to rise above mediocre agents, and truly differentiate yourself as something meaningful. We’re going to dive in to the implications of student debt, how younger users think about things versus experiences, and how they 'hire' services into their lives to solve specific problems they have in their lives. So let’s go.

As a product owner at The New York Times, I hear a lot of research about millennials. Why I have to have a millennials-focused strategy. Why, if I don't have something in place in my business to focus our efforts on millennial customers, I'm pretty much doomed.

To be clear from the outset here, I really loathe the word. My position is that creating value spans all generations, and we shouldn't think of certain buckets of people as an alien species that we must somehow attempt to remotely communicate with. Maybe we should think first about making something that matters. And then, stop putting people in boxes based on how we expect them to behave and what we think they want. Putting the customer at the heart of the experience is something that has always run through the DNA of best in the real estate industry.

And while it's certainly true that an institution such as The New York Times currently has an older-skewing audience, in a similar way that the average age of a Realtor far exceeds that of the average first time home buyer, and that the Times’ churn of older users isn't necessarily being offset by growth in younger users, that doesn't mean we can make broad generalizations about how to 'capture’ or more appropriately connect with younger users.

As The Times aggressively transitions to become more of a digital-first business, just like the real estate industry, this kind of strategy becomes very important in making that switch in offsetting the dynamics of declines in print circulation versus the growth in digital subscriptions. Especially those fueled by engagement on smartphones. This is particularly challenging in an environment where the news is essentially free, everywhere. Running a world-class newsroom of around a thousand people, with bureaus all over the world, just like an international brokerage, is expensive.

And ultimately I believe that there is no 'catch all' approach based on 'how these people behave', so taking the approach of thinking of people in terms of generalized buckets is risky business practice at best, and irresponsible at worst. That said, it's always been the case that generations behave differently from each other. For example, I originally come from a pretty rural village in South West England, and was the first one of my family to ever go to college. But I still remember my father bringing home the freshly bought VCR as if being visited by aliens with some strange time-shifting gift for us. I remember the clock on it blinked twelve o’clock for what felt like years before we figured it out. Indeed, most of the technology that I grew up on and thought was amazing has been replaced by a single device, the iPhone. Remember this guy?

And now that I’m a father myself, I get to see the same process through a different lens. My 5 year old daughter’s completely native with the iPad, excels at Disney Infinity on the Playstation, and seems to be able to navigate Netflix and YouTube with terrifying ease.

So when you see this, what you realize here is that one form of technology or behavior doesn't replace another, it's simply always been an additive process, and this has been a pattern for a long, long time. So let's dive into exactly who we might be talking about here, and let's keep this real estate focused on future first time home buyers.

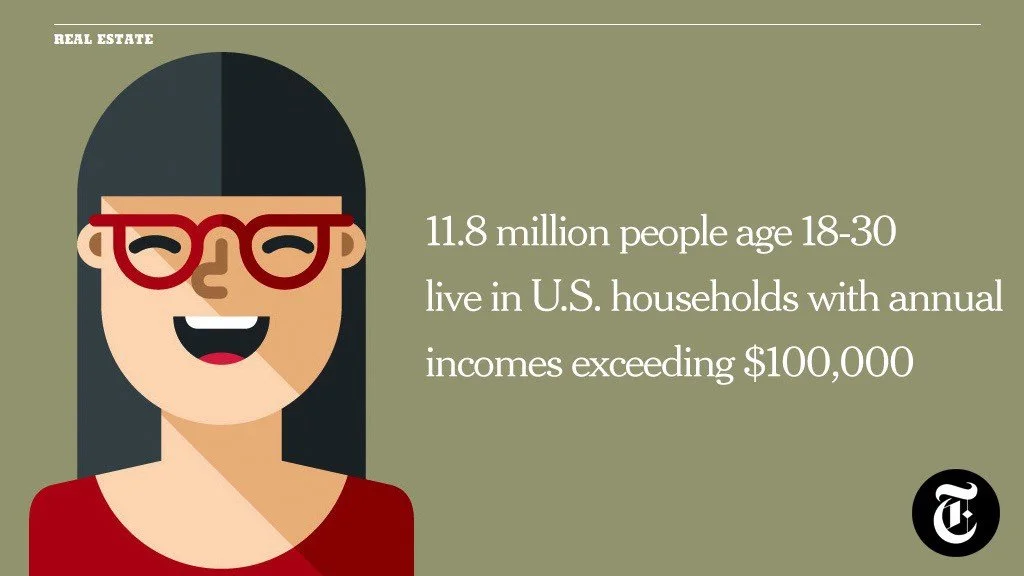

It might surprise you that there are currently 11.8 million people age 18-30 (which we'll reluctantly, reluctantly refer to as millennials for sake of convenience) living in U.S. households with annual incomes exceeding $100,000. Plus, never before has such a large group of young people been raised by wealthy parents: 34% of today’s Millennials have been wealthy throughout their lifetime, say American Express and the Harrison Group.

But these younger customers have a very different relationship to owning things than, for example, my generation (I’m a Gen Xer, just in case there was any confusion there). The relationship to owning things versus experiences is something that's increasingly defining that difference between product and audience growth, or being being put out of business.

When I think about this, my relationship to owning things has always been predicated on those experiences being physical things. Music was an object I bought at the store, and I loved the crackle of the record player and the beautiful sleeve art. For my five year old daughter, music has never been a thing. It's a file on some remote server somewhere, and the idea of owning a library of music is pretty unfamiliar to her.

Similarly with movies. Our house is full of DVDs and a few dusty old VHS tapes. For my daughter, it's YouTube, HBO and Netflix. And also books. I love reading physical books, which are in many ways treated as furniture in our house. My daughter reads on the iPad and discards them when she's done. Think of what this has done to businesses who've not adapted fast enough, previously considered to be industry leaders: Blockbuster, Borders, Best Buy, Polaroid, Tower Records, and dare I say it, Blackberry.

And of course by extension, this relationship also extends to potential relationships with home ownership. The must-haves for previous generations aren’t nearly as important for Millennials. They’re putting off major purchases, or simply avoiding them entirely. And it’s not just homes: Millennials have been reluctant to buy items such as cars, music and luxury goods. Instead, they’re turning to a new set of services that provide access to products without the burdens of ownership, giving rise to what's being called a sharing economy.

The rise of services like AirBnB or Uber are great example of this. Uber in particular, when pressed on why they don't feature any of their drivers on their social media accounts, gave an insightful, powerful answer. Their view is that their service isn't what the user actually wants. What the user wants is what's at the destination. They want to be at home sooner. They want to be with their friends at the bar. Or they want to be enjoying themselves somewhere they're currently not. Uber is simply the conduit to making that happen faster, and that's where they focus.

Think about this in the context of real estate. The online listing itself doesn't have any value. No-one lives in a listing. We live in homes, not houses, and that's what our collective work together facilitates, and actually celebrates. However, the arms race around syndicated inventory has created an unnecessary distraction for many real estate professionals, as several online sites race to the bottom of the web.

I think this really comes down to understanding what's often called 'Inclusive Exclusivity'. Let's frame this as a few 'before and after' comparisons between the broad buckets of baby boomers and millennials.

Boomers find tremendous value in being able to engage with brands that most consumers cannot afford. They use luxury to illustrate their achievement. In short, they think of luxury brand exclusivity as the ability to say “I can and you can’t.”

But as Duke Greenhill writing in Mashable eloquently puts it, when it comes to luxury brands, Millennials have more of a pack mentality. For them, it’s less about “I can and you can’t,” and more about “I can and you should come along.” They see luxury value as a derivative of how many people want something, whether they can afford it or not. This means younger customers demand a very different kind of exclusivity from their luxury brands. this is what we mean by “inclusive exclusivity.” and it's a fairly big leap for traditional brands to often take.

As Greenhill continues, consider Burberry, perhaps the most popular luxury fashion brand amongst affluent millennials. Burberry's revenue jumped more than 20% after including aspirational and real consumers in pioneering social campaigns such as "Art of the Trench." By creating an inclusive platform on Tumblr for brand engagement (and cultivating relationships with aspirational consumers), Burberry effectively increased its exclusivity among consumers who can actually afford their products. As Greenhill illustrates, luxury brands that want to remain valuable among Millennial affluents will steal a page from this playbook and begin tailoring tactics to attract aspirational and actual consumers alike. By enhancing their inclusive exclusivity, they'll increase their brand equity.

Let's keep going here with some more of Greenhill’s thoughts and another example. For Boomers, it is enough to say that a product is expensive because it’s luxurious and exclusive; and it’s luxurious and exclusive really because it’s expensive. Indeed, this Boomer propensity to accept that things simply are what they are is pervasive in the generation’s psychology. This is why Boomers exhibit what seems to be unquestioned luxury brand loyalty, purchasing the same premium brands over and over, saying simply, “It’s the brand I’ve always bought.”

He says “this is not at all the case for Millennials, who scrutinize brands and offer allegiance only to those whose premium price-points are justified” - this is where the rubber hits the road for the real estate industry. They're incredibly fickle in comparison to Boomers, and the sense of loyalty can be eroded in the space of a tweet.

Greenhill concludes by mentioning that millennials demand to know the origin of luxury products — where was it made, how, and by whom? We see this very acutely in New York as you can imagine. “This means luxury brands that want to grow their equity in the near future will have to adjust their marketing message accordingly. They'll have to make emerging affluents aware of the human touch that goes into their products — the craftsmanship involved in the manufacturing process, from first stitch to final sale.” There's an absolutely critical authenticity that these customers are placing huge value upon, and this in particular is where the real estate industry often falls short.

Many realtors talk a big game about 'integrity, unparalleled service and dedicated to excellence'. Everyone's number 1 in their market, and how it's always a good time to buy. But in reference to these customers, you can't just say it, you have to not only mean it, but DO it.

The agents with true, meaningful purpose in their businesses, who actively solve problems for customers, are winning. And it’s driving the mediocre agents out of the business altogether.

What I'm illustrating here is that there's a big difference between real estate professionals talking the talk, and younger customers concluding if the agent can actually walk the walk. And this isn't achieved by a somewhat lame personal branding Hail Mary in an email.

In the Real Estate product group at The Times, we think of this in terms of providing answers to questions the user has in a specific moment within search ‘what does it feel like to live there?’ or ‘how much can I afford?’.

So to return to our generational examples, for Boomers, much of the fun of investing, especially in luxury items is to have what others cannot afford, and to display it. And while this is a pretty broad generalization, these kinds of purchases are seen as a material reward, proof that they have worked hard and earned their lifestyle. As such, luxury brand marketing messages crafted for Boomer consumers have always positioned their products as trophies, as icons of achievement and wealth.

Younger customers seek a very different relationship with luxury brands. They've not yet had time to spend a lifetime accumulating and protecting their wealth, and are still in that discovery mode. That's why affluent younger customers in particular don’t want luxury purchases to be emblematic of who they are, but rather of who they want to be. Luxury is not a symbol of achievement, but rather a promise to one’s self that “I can” achieve.

For the first generation of digital natives, their affinity for technology helps shape how they shop. They are used to instant access to price comparisons, product information and peer reviews, and it's unusual when these kinds of experiences aren't included. Six out of 10 affluent Millennials said they read user-generated product reviews when shopping for luxury goods, where 55% have learned about a product in a store, but preferred to purchased it online, and 18% recommend luxury brand purchases through social network sites.

And let's keep in mind that most of this behavior now happens exclusively on a smartphone, redefining the way brands are using mobile marketing. Two out of five Millennials say would feel anxious without their smartphones. I'm not sure that's just millennials either - I've certainly freaked out when I thought I left my phone on the train.

Now, it is imperative that every platform be optimized for mobile use. Millennials make up 70 percent of consumers who say they are more likely to immediately delete an email if it is not adjusted for mobile use. And what affluent Millennials in particular prioritize is the awesome group photo that can be posted on the network of their choice. They crave experiences. And validation. They'll vacation in Ibiza with their buddies or fly to New York City for the weekend. They see the richness in the storytelling of having an experience, rather than buying one expensive item. And that's a huge difference when it comes to generational comparisons.

According to Unity Marketing, this group will take over the luxury segment by 2018. But keep in mind, these kinds of customers do not seek out products that show off their high status. This isn't about the #brag, or even the #humblebrag in the way that it might be for other generations. Instead they are driven by experiences and opportunities to create memories that they can share with friends.

Writing in Forbes, Larissa Law says that “younger users, regardless of socioeconomic status, attend music festivals such as Bonnaroo or Coachella, but while non-affluent guests stay in basic tents and use communal showers, affluent Millennials pay more for the VIP experience with a gourmet private chef and golf-cart chauffeur service. In fact, nearly all festival and concert organizers have developed “VIP” programs to appeal to these discerning Millennial-aged attendees. Likewise, Millennials may party at the same nightclub, but only the affluent are escorted past the velvet rope to a separate (often elevated) section.” Experience, not things, are the key commodity here.

But of course, while affluence is rising in this part of the population, we can't ignore the elephant in the room, student debt. It's the only kind of household debt that continued to rise through the Great Recession. And now it's the second largest balance after mortgage debt. Aggregate student loan balances almost tripled between 2004 and 2012 due to an increasing number of borrowers and higher balances per borrower.

Lower employment levels and smaller incomes have left younger Millennials with less money than previous generations. As a result, young student borrowers appear to have retreated from both housing and auto markets over the past 6 years. So while we might conclude that younger users are valuing experiences over the consumption of 'things' in their lives, it's also true that with less to spend, they're putting off commitments like marriage and home ownerships in equal measure. To further compound things, 6.7 million borrowers, or 17%, are 90+ days delinquent. Yet 30-49 year olds still have higher delinquency rates.

And as dark as this picture may seem however, an overwhelming percentage of Millennials say they want to own a home at sometime in the future. They crave that experience as part of their lives, and the hiring of a great agent into their lives to facilitate that for them is something they'll do. But the nature of that service is in question, especially as the disintermediation of the agent becomes more and more prevalent through technology.

With higher expectations based on other brands and services they've hired into their lives, it's an increasingly unforgiving process. Think about this in the context of the reviews they leave. There's very little room for the mediocre, and we undoubtedly live in what Jason Calcanis calls 'The Age Of Excellence'. When we talk about trust, or brand loyalty, very often we’re really talking about faith…and the best brands are able to rise above the deafening digital noise and truly articulate purpose to their customers.

The challenge for any brand, be it an individual or a brokerage, is attention. We live in an age of excellence, where if an experience isn’t 5 stars, it’s either ignored, or swiftly forgotten. I mean, who leaves a 3 star review anymore? It’s either amazing, or awful, and there’s no middle ground anymore in an increasingly unforgiving climate, especially online – this is something we feel acutely at The Times as you can imagine.

But this is what real estate professionals have to tackle if they are to win business and rise above the noise. I believe they have to stand for something, and when I think of the best real estate brands, they do this.

But there's some real reasons for optimism here, starting with a brighter economic outlook. Writing recently in the Times’ Real Estate section, Lisa Provost describes how “the job market was particularly unkind to young adults during the recession. According to Labor Department data, between 2007 and 2010 the unemployment rate within this group of younger customers soared to 14 percent from 7.8 percent, compared with 9.6 percent for the population as a whole.”

But as of January 2015, the millennial unemployment rate was down to 9.3 percent. It’s predicted that young adults will enjoy rising wages over the next couple of years, especially given that, according to the Census Bureau, about a quarter of them have at least a bachelor’s degree. But you still have the circumstances of rising wages being offset by student debt repayments though of course.

Also, more are moving out. As Provost continues, “even though job levels haven’t fully recovered, new household formation — which cratered during the recession — is back up to pre-recession levels.”

“One looming question is whether the housing market crash will cause young adults to shy away from homeownership and stick with renting. While it’s still a little too early to say, a good share of young adults are at least thinking about owning, so homeownership is definitely on the radar. In a recent survey, 32 percent said they were saving for a house, but on the down side, 22 percent said they were not saving at all.”

So when it comes to thinking about creating wonderful real estate experiences for our customers, and our younger customers in particular, we’re all guilty of making assumptions. For example, ‘this is how millennials behave’, ‘here’s what renters think about the market’ or the evergreen ‘here’s where all the foreign buyers are coming from’.

These kinds of personas tend to be predicated upon our own stereotypes and personal experiences, and are often just made up. While some people may behave in ways which confirm your conclusions, a review of facts show these stereotypes to be what they are: anecdotal at best and often incorrect.

The tendency to fall into patterns of grouping together vaguely outlined personas and drawing broad conclusions around them is something that can define a poorly designed user experience, especially in real estate. When we think about these kinds of problems in the product group within Real Estate at The New York Times, we deliberately try to implement an approach which gets us thinking differently about how customers consume experiences.

Often, because people are so focused on the who and how, they totally miss the why. When you start to understand the why, your mind is then open to think of creative, collaborative and original ways to solve the problem.

In The Times product group, we believe that products get ‘hired’ into people’s lives to solve a problem. For example, what to cook tonight, what to watch, or where to live. The desire to solve a problem is the catalyst for purchase and use of a product. We call the solutions to these problems ‘jobs to be done’. And thinking in these terms forces us not to make too many assumptions about our users.

Jobs To Be Done is a set of ideas about what causes us to make decisions around consumption. It asserts 3 things:

People don’t simply buy/use products and services, they ‘hire’ them to get a “job” done in their life.

People encounter situations that drive and shape their need for these jobs.

People have criteria (sometimes conscious, but often not) to evaluate the success of a job.

The Jobs To Be Done framework helps us to understand the forces helping searchers move toward a purchase decision, and the most important ‘jobs’ that these people need to get done as part of that process. For example, not just thinking about the search process, or even searching online itself, but actually finding something they want to go and see in person. So what we’re describing here is a way to capture and understand motivation, and there are many parallels with the role of the agent in the home selling and purchasing process here.

For example, thinking about why a customer has ‘hired’ the services of an agent into their lives, they’re not just looking for someone to facilitate the transaction of their home, they’re looking for much, much more than that. They’re looking for a service which is going to hold their hand through the process, eliminate risk, provide guidance and insight, and ultimately make the experience an enjoyable, exciting one. One that facilitates something else in their lives. And following the order of our previous assertions, it’s these kinds of criteria by which the success of the agent is often evaluated. Not ‘did they sell my house’, but rather ‘to what extent did they succeed in completing the job I needed done in my life?’

A simple way to frame this is as a sentence:

When (the situation), I want to (the motivation), so I can (the expected outcome).

So for example: “When I’m looking for a 2 bedroom, 2 bathroom home in Sarasota for under $750,000, I want to make sure there’s enough room for me to build that man cave of my dreams, so I can finally have game night with the guys in my own place.”

See how the motivation here is getting enough room for game night, not the home purchase? This approach can be really helpful in thinking about your real estate marketing because it makes you think about motivation and context. So when we’re designing search products, or services for finding a home at The New York Times, we frame every design problem this way, focusing on the triggering event or situation, the motivation and goal, and the intended outcome.

Taking a step back and understanding the individual motivations at play, and working with the idea of ‘jobs to be done’ can be a powerful way of re-framing your business. Think about this the next time you’re working with a customer who’s really just not sure what they want. What’s really driving and shaping their need to work with you? What assumptions are you making that might not be true? What’s the ‘job’ that they’re really hiring you into their lives to get done, and how are they evaluating the success of that process?

Is it a home transaction, or is it more than that?

I hope you enjoyed my stories, thank you.