The Greatest Movie Never Made

Kubrick’s Napoleon (1969) vs. Bondarchuk’s Waterloo (1970)

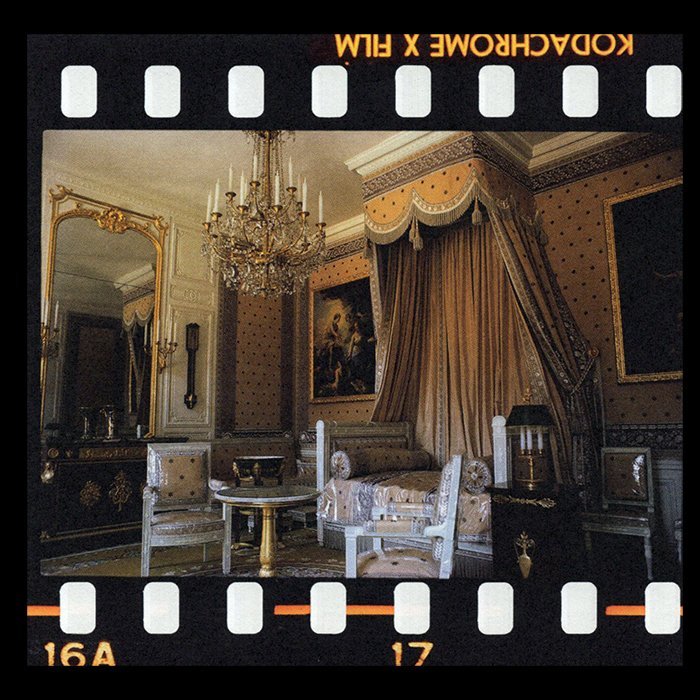

In late 1969, Stanley Kubrick was busy. His career-defining 2001: A Space Odyssey had been an enormous directorial and technical success, he was in the middle of editing the dystopian A Clockwork Orange, and beginning to circle what he thought would be his next grand project, a definitive biographic story of Napoleon. Like all Kubrick projects, especially those following 2001: A Space Odyssey, the process for developing the script, and the sheer effort which went into the production was total. For years, Kubrick had planned to create a biographical film of Napoleon’s life, and had engaged hundreds of production staff in gathering as much information as possible about the era. From costumes, interiors, historical records, surviving written evidence, academic historiography, everything was completely exhaustive, and all of it would go into the creation of what Kubrick believed would be one of the greatest historical films ever made. Weighing in at over 830 pages of production notes, pre-production stills, location scouting, script drafts, correspondence and reference material, all of Kubrick’s work has recently been gathered together into a single volume.

It’s a fascinating artifact of a movie which was never made, and reveals not only the pressures of budget and the wrestling with studio executives, but Kubrick’s seemingly endless curiosity for accuracy in historical detail. From what Napoleon ate every day (and how), to the specific, daily documented movements of those around him and more broadly elsewhere in early nineteenth-century Europe. The gathering of material is immense, with tens of thousands of images, written documents and scholarly perspectives. In immersing himself completely in the material, Kubrick would be able to create the definitive document of one of history’s most fascinating and flawed leaders.

In gathering all of this documentation, he created a highly detailed card catalog to make sense of the themes and categories of activity throughout Napoleon’s life, and planned to put these to work on location in Romania, where most of the movie was planned to be shot (an unusual departure for Kubrick given his preference for shooting near his ex-pat home in Borehamwood, England), and where he had engaged the support of the Romanian army. In total he had commitment for over 40,000 soldiers and over 10,000 cavalrymen, all of whom would wear paper costumes to reduce the cost of needing to make the uniforms from real material. This is before any digitally-generated capability, so any grand shots of armies on the move, large-scale battles, or crowds welcoming Napoleon home would need to be shot live. Nowadays we take such shots for granted, even though we know they couldn’t possibly be real, but in the early 1970s everything needed to be filmed as it happened in the real world, which meant real humans being directed.

Kubrick’s non-committal in his production notes as to casting, but there’s some brief conversation around the casting of David (Barbarella, Blow-Up, Alfred the Great) Hemmings in the title role, who’d recently spent time filming the semi-related Charge of the Light Brigade and had some experience in the depiction of flawed military leaders. Jack Nicholson seemed to be a front runner by the time production was abandoned. Audrey Hepburn had been approached for the role of Napoleon’s wife Josephine, but had politely said no.

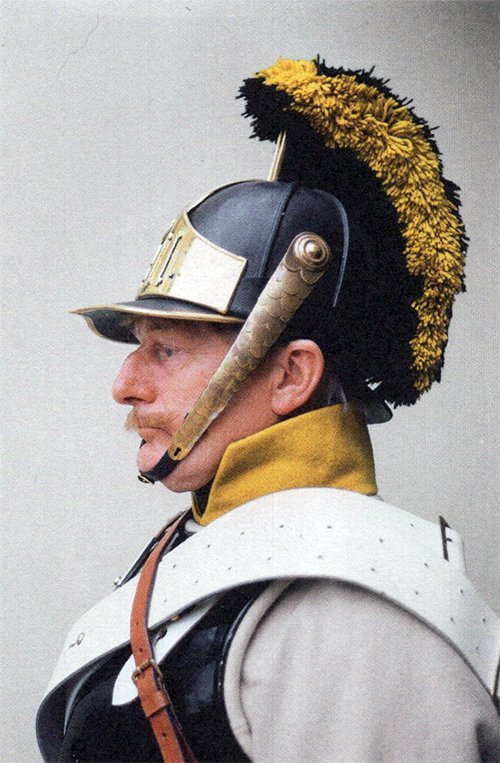

Spending time with the production materials is a real treat, and one where you feel Kubrick’s hand in every location scout’s found image, every costume test, and every piece of written correspondence. Everything already feels like a completely realized Kubrick movie. The location stills have an attention to detail to them that’s so cold it’s cool. The endless costume tests, many of which are taken from varying distances to understand how much detail would be visible on screen and essentially how much they could reasonably get away with for the costume budget, are incredible in their breadth and scope, taking in different armies, nationalities, regiments, ethnicities, genders and occupations. And like most Kubrick projects, the result is completely immersive, consuming the viewer in the material, and drawing them in with such incredible detail and nuance, and in this case historical accuracy, as to be so overwhelming we’ve no choice but to take it as truth. At this point the movie stops being a movie, and the story truly becomes magic.

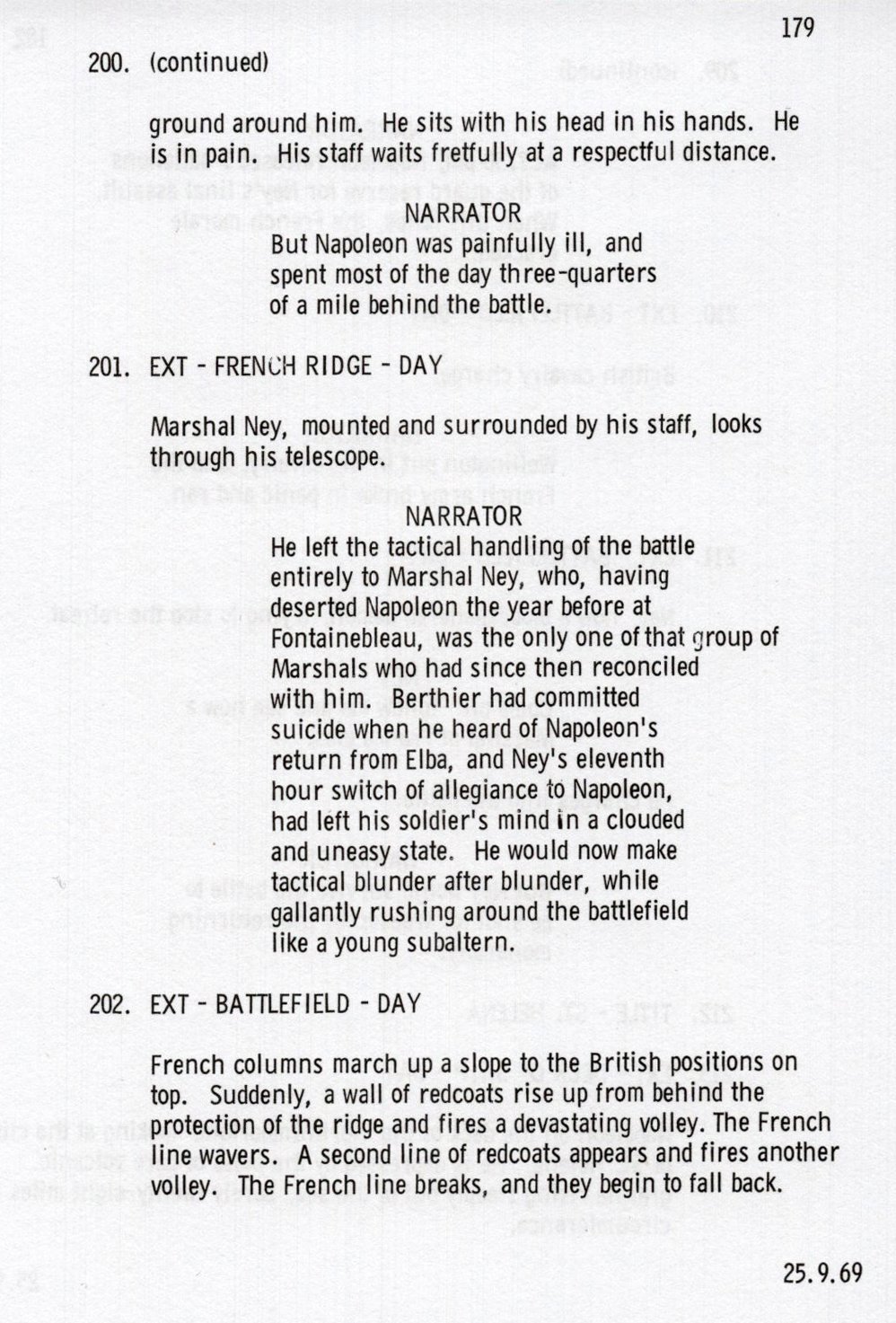

Kubrick’s script itself is fascinating. Essentially a singular chronological narrative spanning Napoleon’s childhood in Corsica to his death in exile on St. Helena. It takes in his early military training, his rise in influence during the French Revolution, through the carnage of Austerlitz, Trafalgar and the disastrous retreat from Moscow. There’s attention given to his escape from Elba, Josephine’s infidelity, and of course, his final defeat and capture by the Allied British and Prussian armies at Waterloo in 1815. It’s expansive in scope, and pulls in many of the details we see getting clarified in Kubrick’s notes elsewhere to distinguished historians he’d engaged as consultants. Many of the script details, especially the use of narration as a guiding force throughout the film, would later resurface in Kubrick’s 1975 Barry Lyndon, which was able to lean on much of the abandoned material Kubrick had assembled, with particular reference to the military engagements which bring Ryan O’Neal’s Redmond Barry to prominence early in the film.

But by 1970 production concerns were escalating, and it was clear that filming on location at such enormous scale was going to be cost-prohibitive. Coupled with the commercial failure of Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo the same year, which Kubrick had called ‘a silly film’ and was much smaller in historical scope but enormous in its use of 17,000 Soviet Army extras, filmed in Ukraine and famous for its incredibly lavish battle scenes. Kubrick ultimately abandoned the Napoleon project in favor of an smaller but no less ambitious adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Luck of Barry Lyndon, which bridged the gap in Kubrick’s movies between the dystopian horror of A Clockwork Orange and the psychological horror of The Shining. Over time, there have been several attempts to rehabilitate Kubrick’s script, most notably by Steven Spielberg in 2013 for HBO, but none of them have so far come to anything, and of course, there are some enormous cinematic boots to fill in doing so. Kubrick’s Napoleon continues to fascinate as one of the most incredible movies never made, but the archeology and artifacts left behind, surgically documented and catalogued, give us an amazing window into what could have, would have, should have been.

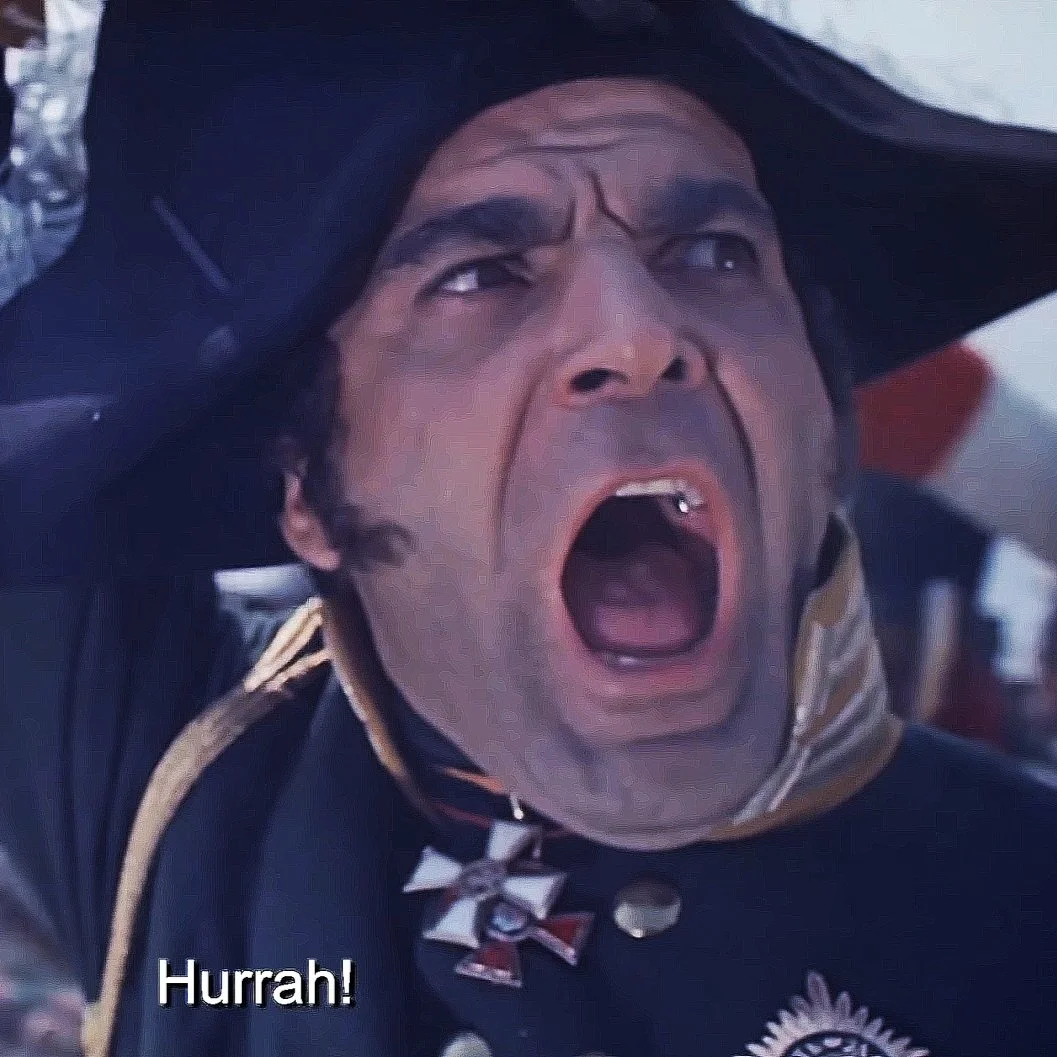

If Kubrick’s Napoleon promised to be the definitive historical document of the French Emperor’s life, then Bondarchuk’s Waterloo is the memory of the end of that story delivered with extravagant pomp and excess, committing to film some of the most incredibly complex and astonishing scenes in service of the memory, rather than accuracy, of the events of Sunday, June 18, 1815. The main events of the film concern the tactical and often bloody maneuvering between the British and the French during the battle, preceded by the briefest of historical scene-setting introductions to both political climates in the early nineteenth century. Strangely out of place in particular is a cameo from Orson Welles as Louis XVIII of France, who in many ways played himself as the tired, overweight, last gasp of an era long since condemned to history.

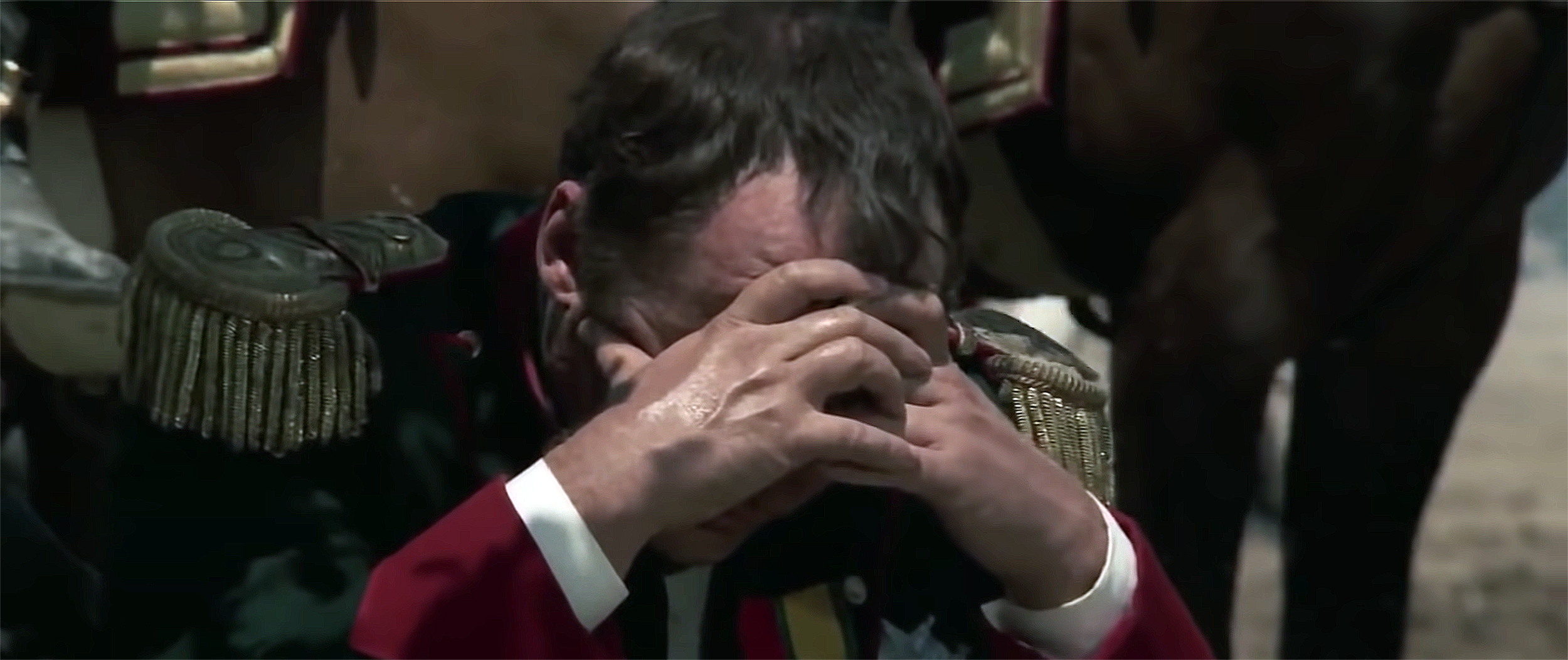

But to be clear, Bondarchuk’s Waterloo is epic. Rod Steiger is incredible as the tortured, increasingly desperate Napoleon, a proud man of the people consumed by his own greatness, antithetical to the upper class indifference of Christopher Plummer’s Duke of Wellington, who cares little for the expendability of his own men, and treats the carnage as no more than the pursuit of a fox during an aristocratic hunt. We hear the inner monologues of both leaders frequently throughout the movie, revealing their inner thoughts and fears, as well as their next moves. We as the audience are privvy to the anxiety neither of them can show their armies. Once the scale of both operations have been established, an opening cannon is fired, and the battle begins. Wellington’s men synchronize their ornate pocket watches, and the moving of chess pieces among the Belgian fields of Waterloo opens. Infantry on both sides march to the beat of adolescent drummers. Cavalry anxiously await instructions. Cannons test each other for weakness.

True to historical accuracy, most of the fighting takes place around the farmhouses of Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte, but we are witness to the switching back and forth between Wellington and Napoleon’s perspectives as events unfold, as both sides eagerly await the arrival of reinforcements. Napoleon in the form of Marshal Grouchy’s army, a third of the entire French military, who has been pursuing the Prussians under General Blücher, for whom Wellington waits and buys as much time as he can. Heroism is graphically depicted on both sides, with both French and British fighting to a bitter, bloody end where the pyrrhic winner is going to be the one who dies the least. Regiments are shredded with cannon fire, and cavalry cut down anything in their path. In one of the most memorable scenes, there is a reenactment of the infamously disastrous cavalry charge of the British Scots Greys regiment. As one of Napoleon’s generals, Marshal Soult calls them ‘they are the noblest cavalry in Europe, and the worst led.’ As the charge gathers pace, there’s an incredible set of slow-motion shots of the front of the cavalry charge, with direct reference to Elizabeth Thompson’s 1881 painting ‘Scotland Forever!’, one of the most iconic and memorable images of the entire battle. As we exit the dream sequence, the cavalry charge head-first into the French cannons, are cut down, and while attempting to flee, their aristocratic general is lanced to death and ends face down in the mud.

As the film crescendos, so does the music, but also the scale of the spectacle. The French attempt a desperate cavalry charge in efforts to finally break the British squares, but are deceived by thousands of soldiers hiding behind a hill in the tall grass, just as the Prussians arrive to finish everything and end Napoleon’s dreams of empire. In a brave but ultimately fatal attempt at ending the battle, the British offer surrender to the exhausted remaining French soldiers, who refuse in a way only they can. The British cannons line up, and in one giant burst of fire, the remaining French soldiers are no more.

There’s a tremendous amount of historical creative license taken within Waterloo. Some characters are aggregates, pieced together from different dignitaries that may or may not have even been there. The topography of the battlefield was almost certainly not the one depicted in the rolling hills and fields of Ukraine where the movie was filmed, despite Soviet attempts in pre-production to flatten them. And the field itself was incredibly wet and muddy, which would have dramatically hampered fast-paced events such as cavalry charges or the swift wheeling to-and-fro of the respective artillery. But if that’s the point in Kubrick’s Napoleon, to suspend our disbelief to such an incredibly accurate extent as to place us exactly in that precise time and space, Bondarchuk’s battle gives us an equally powerful simulacrum of the day’s events. A strong enough feeling of the horror of battle, and the thoughts and feelings of its main protagonists. It might well be the fast food to Kubrick’s prime rib, but it’s no less enjoyable, and certainly no less of a technical achievement.

I love Barry Lyndon, but feel Napoleon would have been even better. Increasingly separated from both the studio system and the concerns of the commercial outcomes of his work, Kubrick was entering a period of almost complete directorial autonomy, something he used to tremendous effect with the (only) four movies he’d create after 1971’s A Clockwork Orange. With near-limitless budgets, and broad latitude to create the stories he wanted to tell, such creative freedom also sadly feels like a relic of the past. We can create visually similar special effects to the ones captured in Waterloo, or aspired to in Napoleon, but we know they’re not real, and so we already miss something. But it also feels as though such grand cinematic storytellers are also near extinction. Spielberg, Scorsese and Lynch, Tarantino, Herzog or Moviegoer favorite Wes Anderson. None of them have the enormous strength of curiosity, drive, and sheer will to dare to approach a subject like Kubrick. And being able to spend time with his production archives, aside from being an enormous treat, gives us a starkly clear reason why that’s the case.