The Satisfaction of Barry Lyndon

Stanley Kubrick, 1975

I always think of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon as the Kubrick movie everyone forgot. While it has all the signature trademarks of a Kubrick classic, from the emotional detachment that’s so cold it’s cool, to the innovative cinematic techniques, extreme points of tension and beautiful photography, it’s often eclipsed by his films that came before and after it. 1975’s Barry Lyndon sits between the notoriously dystopian A Clockwork Orange (1971) and the eternally terrifying The Shining (1980). In a career of classics, also amongst them 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Barry Lyndon often gets overlooked, especially in an era of syndication, streaming and subscription.

Much has already been deeply documented about Barry Lyndon. From the exquisite costuming to the invention of low-light cameras which enabled the crew to authentically shoot by candlelight. From the Hogarth and Gainsborough inspired painterly set pieces to the questionable performance of Ryan O’Neal as our eponymous anti-hero on and off the set, at the peak of his success and fresh off the career highs of Love Story (1970), What’s Up Doc? (1972) and Paper Moon (1973). From its genesis as an abandoned Napoleon biography to Kubrick’s creative departures from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 original novel.

Barry Lyndon’s pacing isn’t as methodical and drawn out as 2001: A Space Odyssey, but it’s a slow movie, especially as Kubrick ratchets up the political and emotional tension between the Lyndons and the Barrys towards the film’s crescendo. Shots linger, looks hold uncomfortably long, and it takes an eternity by contemporary standards for actors to cross a room. Violence, betrayal and desperation are all here too. But taking in all of Kubrick’s most memorable cinematic scenes, I believe that Barry Lyndon’s final duel holds its own among the best. And of course, Kubrick’s got a lot of these in his library. From HAL’s willful murder and subsequent lobotomy to the bathroom murder suicide of Full Metal Jacket, from a nuclear bomb being rodeoed into oblivion in Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) to the horrific sequences of violence in A Clockwork Orange, from the blood pouring out of the elevators in The Shining to Tom Cruise not knowing the second password in Eyes Wide Shut, it’s a career defined by scenes that keep us awake at night.

One such deviation from the original material is Barry Lyndon’s final duel, which takes place in an old church barn, with doves circling and the slow, ominous, visceral drum beat of Handel’s Sarabande playing out between interminable silences. It takes place between a now adult Lord Bullingdon, the recipient of much of main character Redmond Barry’s violent wrath as a child as Barry climbed the social ladder as his abusive stepfather. He has returned on the desperate wishes of the Lyndon family priest, Reverend Samuel Runt, exhausted from seeing Barry gamble, drink and whore away the family fortune. Lord Bullingdon, a precocious child extremely close to his mother and devoted to his deceased father, and for whom Barry has conveniently stepped into his shoes as cruel stepfather, was expelled for an egregious pattern of social disobeyance of his new father, culminating in Barry publicly beating him. Bullingdon is back for satisfaction, and can take it no more. Demanding revenge, he finds Barry worn out in a drinking den, and requests his satisfaction in a duel.

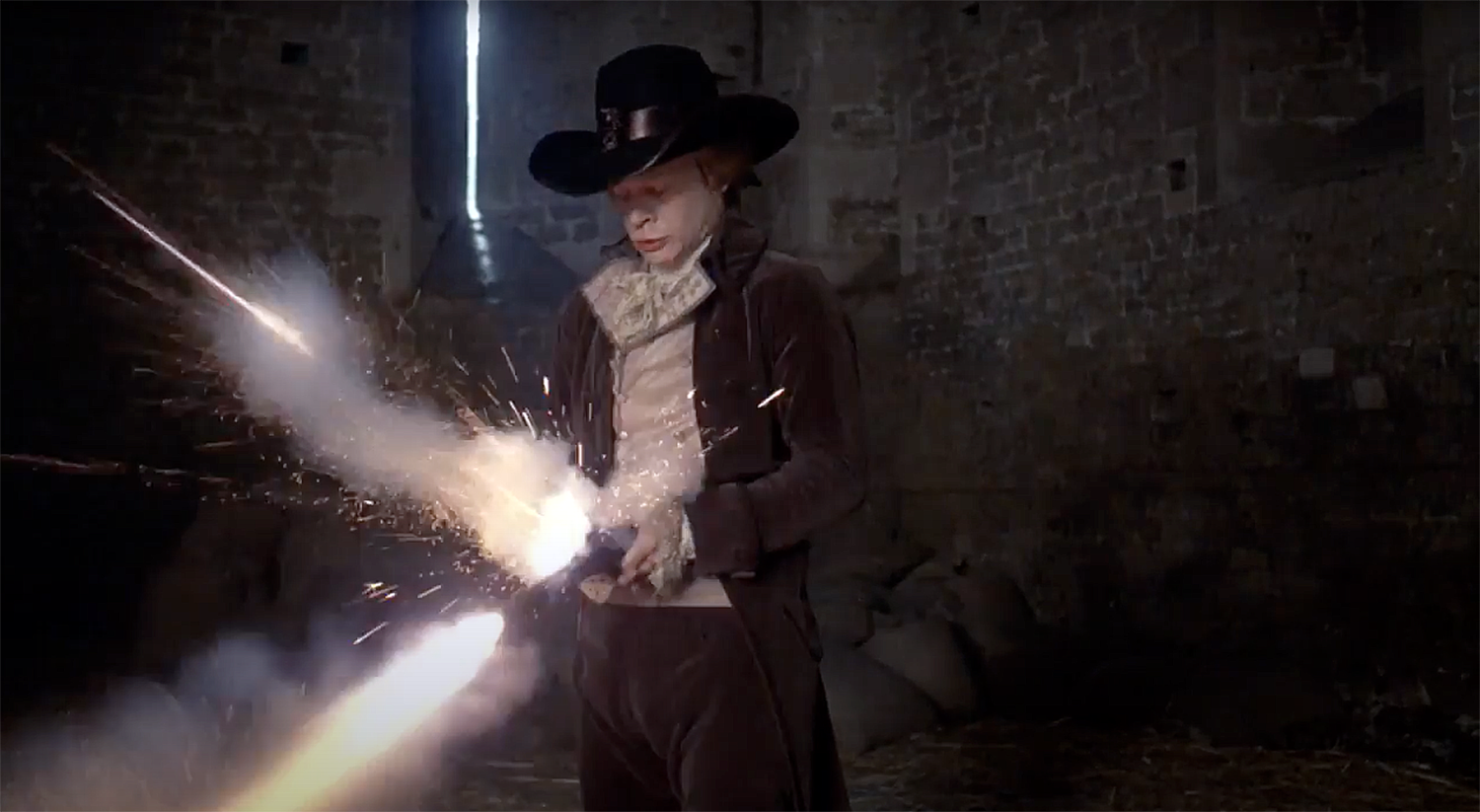

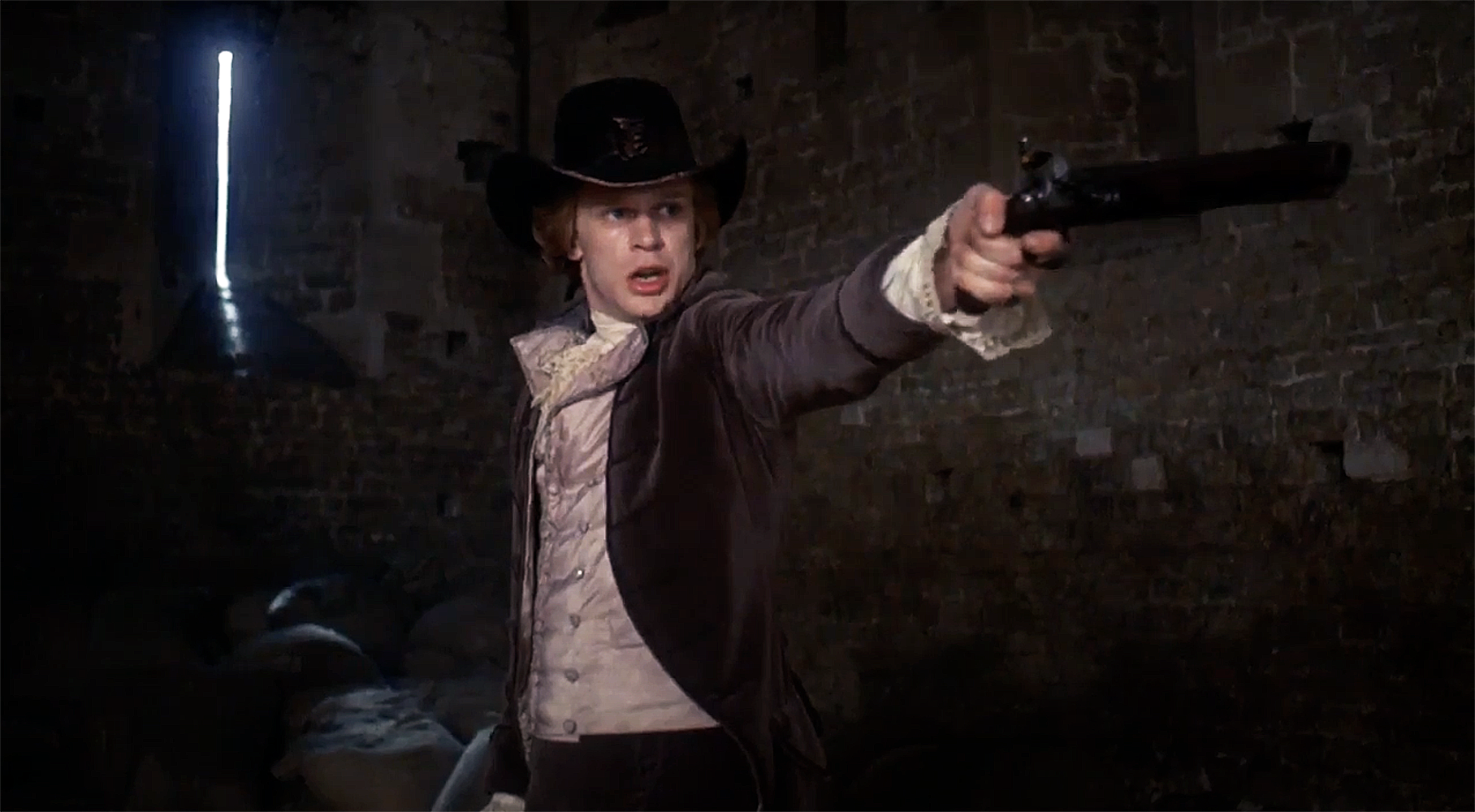

The ten minute duel sequence draws us in with an explanation of the rules from the attending officials, a critical coin toss to see who’ll receive fire first, and then the marking of the ten paces of ground. First-time viewers have no idea what’s coming, a Kubrick speciality. For as expansive as many of the beautiful landscape scenes are in Barry Lyndon, this setting is claustrophobic, and an immediate signal that something awful is about to happen. Bullingdon is first, with Barry set to receive. But as he prepares to fire, the pistol unexpectedly discharges, and his turn is taken. He blames an ill-prepared firearm, and asks to go again. The officials say no, he’s had his turn, and Barry now gets to fire. As they both take their ground for the second time, Bullingdon’s stomach fails him, wrought with nerves at the prospect of his imminent death. He knows of Barry’s military background, and he fears the worst. The officials count down to the moment, and with purpose, Barry fires into the ground, spoiling his shot. Without a word, Barry signals that despite the differences between them, he bears no ill feelings, and ultimately doesn’t want Bullingdon dead. The officials, stunned at Barry’s generosity, ask Bullingdon if he has therefore received the necessary satisfaction.

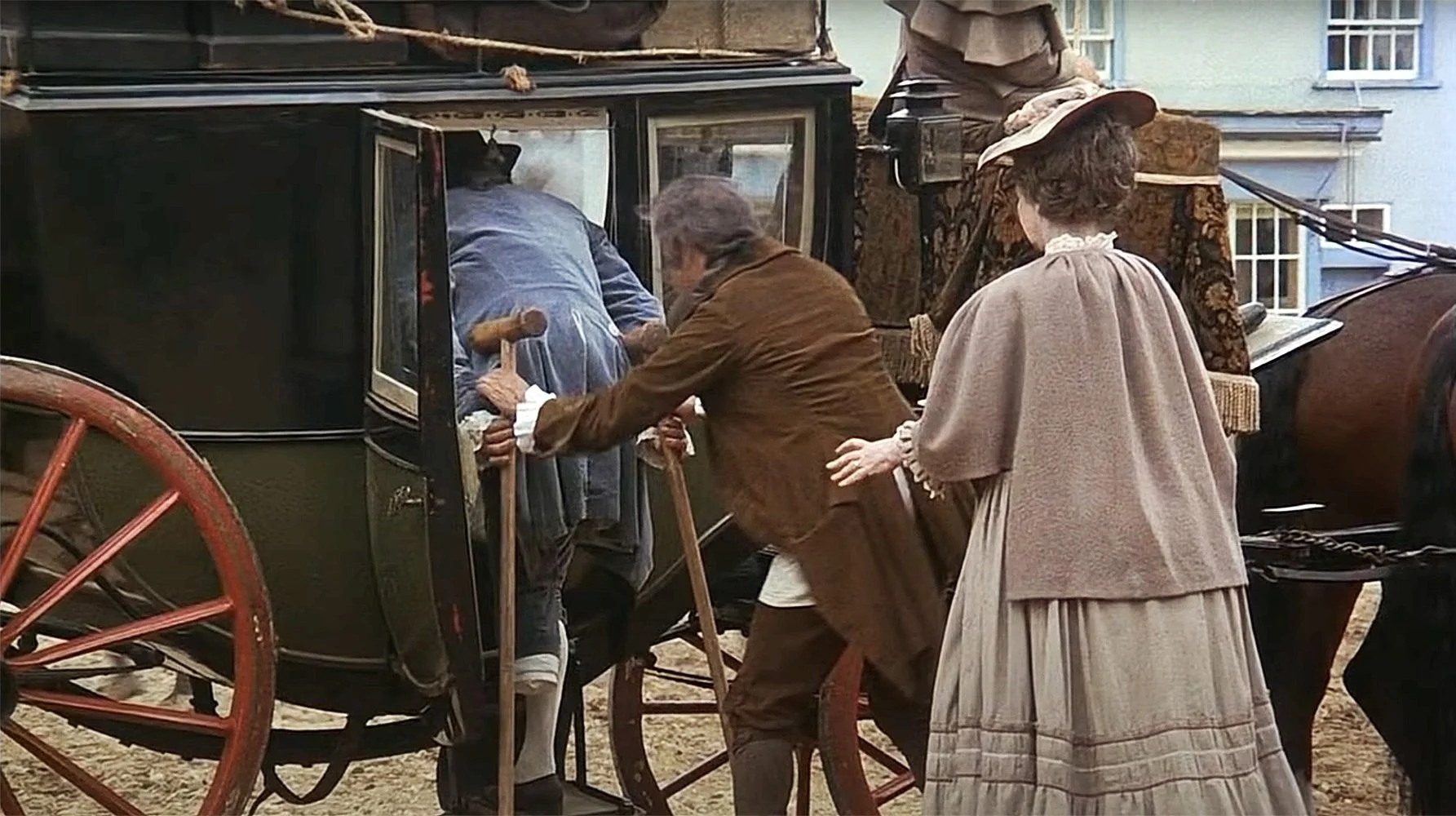

What happens next is one of the best moments in all of Kubrick’s movies. In all of movies. Bullingdon slowly shakes his head, and says no. All the resentment at Barry’s cruelty, all the anger at the mistreatment of his mother and his estate, and all the desire for revenge built up over years of rumination and retribution is finally here. His legacy, his social standing, and his opportunity to exorcise the emotionally abusive cancer that has plagued him since childhood are all within reach. This time he carefully cocks his pistol, Barry turns to receive his fire, and Bullingdon, shaking with nerves, fires into Barry’s leg, who collapses to the ground. The injury isn’t a fatal one, but it’s the end of Barry’s career as a social climber, and pretty much the end of Barry altogether. He retires to a nearby inn, his leg is amputated, and there are some conciliatory pieces of distant future narration, voiced over by the wonderful Michael Horden. The film dramatically freezes, and our story moves on. The last we see of Barry is him hobbling into a carriage to leave England for good.

The duel in Barry Lyndon is one of the most Kubrick of all Kubrick moments, and I’d argue one of the best of all his movies. It’s the kind of cinema you watch through your fingers, the kind that quickens your heart, and the kind that you think about long after the credits have rolled. It’s ripe with betrayal, revenge, coldness and method, all characteristically juxtaposed with beautiful cinematography, historical accuracy, and meticulous editing. It holds its own with all of Kubrick’s other movies. But if we believe this to be true, then why is it eclipsed by so many of his other films?

It’s a period drama, and period dramas mean something different these days. Not just in terms of expansion of empire in an era of reparation, but also that period dramas in modern cinema are rarely associated these days with the military. There are of course exceptions, but without an Austen or Bronte-inspired origin, there is little commercial appetite for pursuing an audience interested in this kind of story. Therefore in this climate, remakes become rampant. There have been seventeen film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice for example, five of Sense and Sensibility, and over seventy of Jane Eyre. Thackaray’s hanging in there with about a dozen versions of Vanity Fair, but in general it’s not a diverse storytelling field, and the perpetual commercial remakes are cynical and weak.

Pacing is also important here. It’s a slow film, building with purpose towards a crescendo that’s absolutely worth it, but requires the investment of time, something we have less and less of in an era of push notifications, social feeds and intrusive advertising. With more and more of our attention spent on smaller and smaller consumption, devoting time to purposeful cinematic experiences becomes a luxury, but something few of us can afford.

Barry Lyndon also suffers from the immediate lineage of the films around it in Kubrick’s output. Preceding Barry Lyndon is A Clockwork Orange, which for different reasons doesn’t tend to run in syndication but is widely known through its notoriety and having been banned for several decades, is also uniquely visually stunning, but ultimately evergreen in its themes of punishment, government influence and the corruption of the youth. I’d argue that the stills of Alex in his full Droog gear outpace Ryan O’Neal in his period finery for use in modern media. And then succeeding Barry Lyndon is The Shining, which runs and runs in syndication, especially around Halloween, and is generally accepted as one of the best of its genre. Nicholson’s performance as the deranged Jack is stunning, and the visuals and cinematic innovations, particularly around the use of the steadcam are incredible. Nicholson’s peek through the broken bathroom door as Shelly Duvall screams for her life is one of the most recognizable cinematic images in history.

So put away the phone, dim the lights, clear the calendar and make sure you’ve eaten. Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon is deservedly recognized as one of the greatest, most innovative moments in film history, but it’s specifically Bullingdon’s small shake of the head during the final duel that represents so much, unleashes so much anger, and stands for all the cold cruelty and emotional abuse in his family’s life that’s the real moment worth waiting for.