Withnail & Us

Easily one of the most tender yet acerbic, loving yet sarcastic, and hysterical yet desperate stories you’ll ever watch, Bruce Robinson’s 1987 autobiographical Withnail and I has always been one of my top five all-time movies. The story of two out-of-work and down-on-their-luck actors in London’s Camden Town at the tail end of the sixties, it features some of the best (and most quotable) dialogue ever to be put on screen, as well as outstanding performances from the two main protagonists, Richard E. Grant (The Player, Gosford Park, The Rise of Skywalker) as the entitled, dramatic Withnail, and Paul McGann (Doctor Who, Alien 3, Holby City) as ‘I’, who is never referred to by name in the movie, but who we know from Robinson’s screenplay is called Marwood.

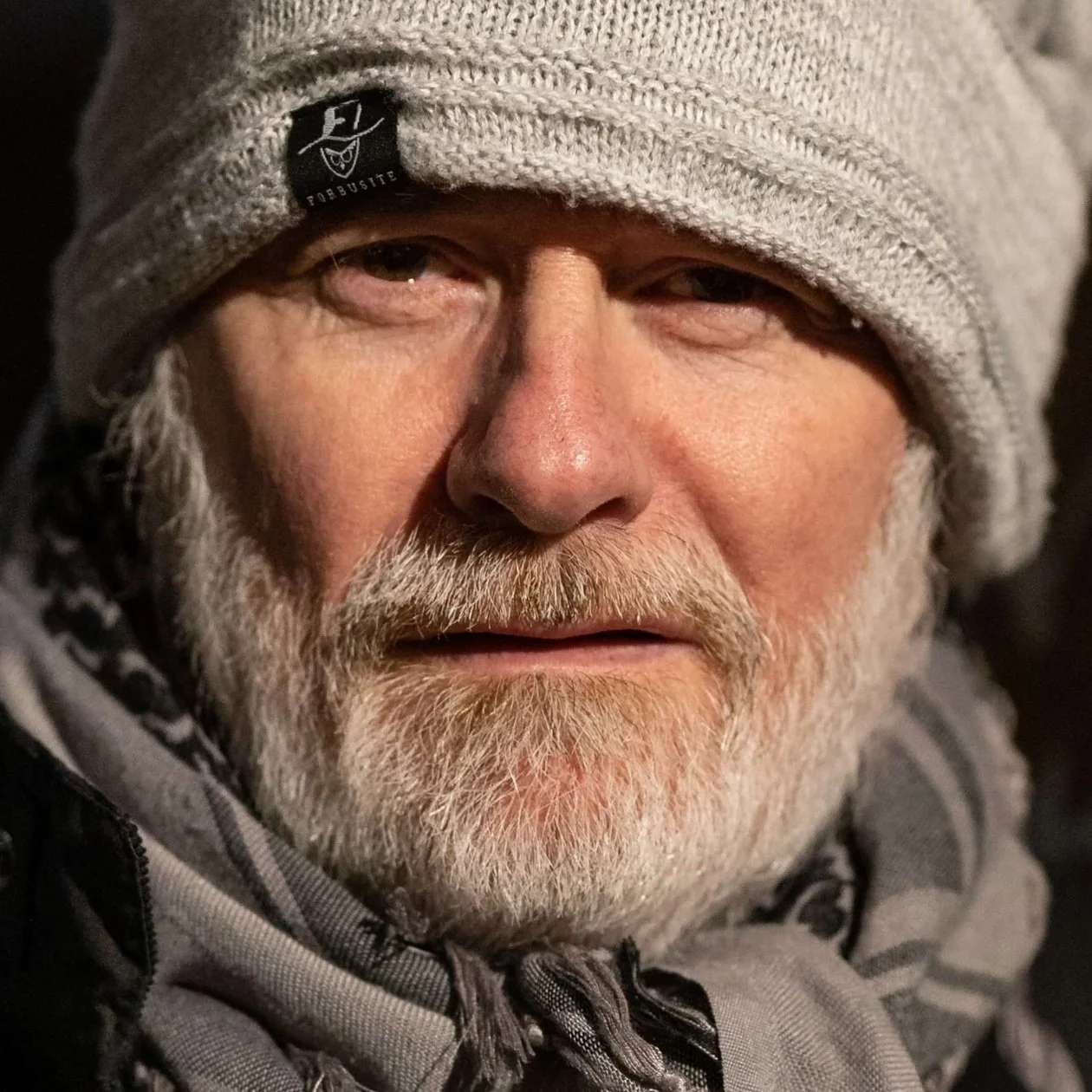

The plot is simple. Two actor friends, living in extreme squalor and ‘reduced to the states of a bum’, strung out on drink, drugs and the end of the sixties party, decide to take a mental and physical break from it all at Withnail’s uncle’s cottage in the countryside. Escaping the local wankers and all of London’s desperate, crumbling, drug-addled trappings is not just what they want, but what they need. Convincing Withnail’s flamboyant and eccentric Uncle Monty, brilliantly and at times, terrifyingly played by Richard Griffiths (Harry Potter series, The History Boys, Sleepy Hollow) to lend them the key through deceptive means that they’ll later come to regret, they set off for a week away together. They ride off in Marwood’s beat-up Jaguar, shouting at passers-by while Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Chile’ blares from the radio. Indeed, there’s some wonderful music choices throughout the film, directly influenced by Handmade Films’ (Monty Python’s Life of Brian, Time Bandits, 127 Hours) producer George Harrison. Even Ringo gets an executive producer credit.

Withnail’s the more charismatic, outspoken and reckless of the two, and comes from a background of wealth and privilege, whereas ‘I’, based on Robinson himself, is more thoughtful, and easily the more practical of the two. Arriving at the cottage in driving rain, they slowly acclimate themselves to life in the countryside, and all the cultural differences that entails from their life in the city. We see them visit the local pub, with its colorful cast of regulars, as well as hysterical interactions with farmers and an intimidating, mysterious local poacher, who they enlist to give them some food. They talk about their careers, or lack of them, with Withnail’s pretensions and delusions of stardom on full display, literally screaming from a hilltop as to his impending stardom. But as they settle into life away together, and begin to relax, their peace is disturbed one night by the violent arrival of Uncle Monty, who Withnail has convinced and coerced into joining them with the nefarious promise of I being ‘available’ for him.

Indeed, Uncle Monty’s intentional misperception of Withnail and I’s homosexual relationship, and the deliberate deception that I has a sordid past of ‘toilet trading’ causes Monty to break down the door to I’s bedroom one night, fueled by a lifetime of rejection and societal concealment to declare his true intentions. “I mean to have you, even if it must be burglary”. The exchange of unrequited love and Griffiths’ portrayal of Monty’s lifelong desperation for love and affection are fantastically played with sensitivity and genuine tenderness by Griffiths. And despite his violent advances, we feel true sympathy for Monty. I, rebuffing his advances and explaining that he and Withnail are not in fact lovers, leads them to have to return to London, with the added twist of I now having successfully found a job in a play. Withnail already knows their time together is coming to an end.

Their return to London, complete with a stop at the local police station for an unsuccessful if highly creative sobriety test, finds Danny the Drug Dealer and his associate ‘Presuming Ed’ installed in their apartment. The sixties party’s most definitely over by this point, as they descend even deeper into drug use, desperation and the squalid hopelessness of their situation. The exchanges between Withnail and Danny have some of the best dialogue of the film, as well as the appearance of Danny’s ‘Camberwell Carrot’, the delights of which I will leave for you to discover on your own when you watch the movie. I’s agent calls to confirm his job in a West End play, and he begins his preparations to leave. Withnail, subdued and sinking deeper into drink and drugs, resolves to send him off and at least walk him to the station to say goodbye.

There follows some of the most tender exchanges between the two friends, who both know this is it for them. They know they will begin to drift apart, but will always have fond memories of each other. We don’t see it, but already know the paths both of them are going to take in life. As the movie crescendos in a rainy Regent’s Park, Withnail delivers the soliloquy from Hamlet, not just to a small audience of wolves from the adjacent zoo, but also directly to us as the audience, bowing gently to wish us well as the credits roll. It’s a heartbreaking, brilliant close.

Withnail and I is a hysterically funny, tender and expertly written movie about the fine, often confusing line between love and friendship, especially between those who share finite, intense periods of time together. It always reminds me of my first time at University back in the nineties, where as a student you enjoy a brief, but incredibly intense, formative and meaningful set of relationships, and then when it’s over everyone scatters like ants under a lifted rock. Only a few keep in touch, the ones who want it, and still mean it, but it’s hard not to be nostalgic for that time again later in life. Of course, you can never go back, and even if you did, you’re different.

Withnail & I is currently streaming on HBO Max.